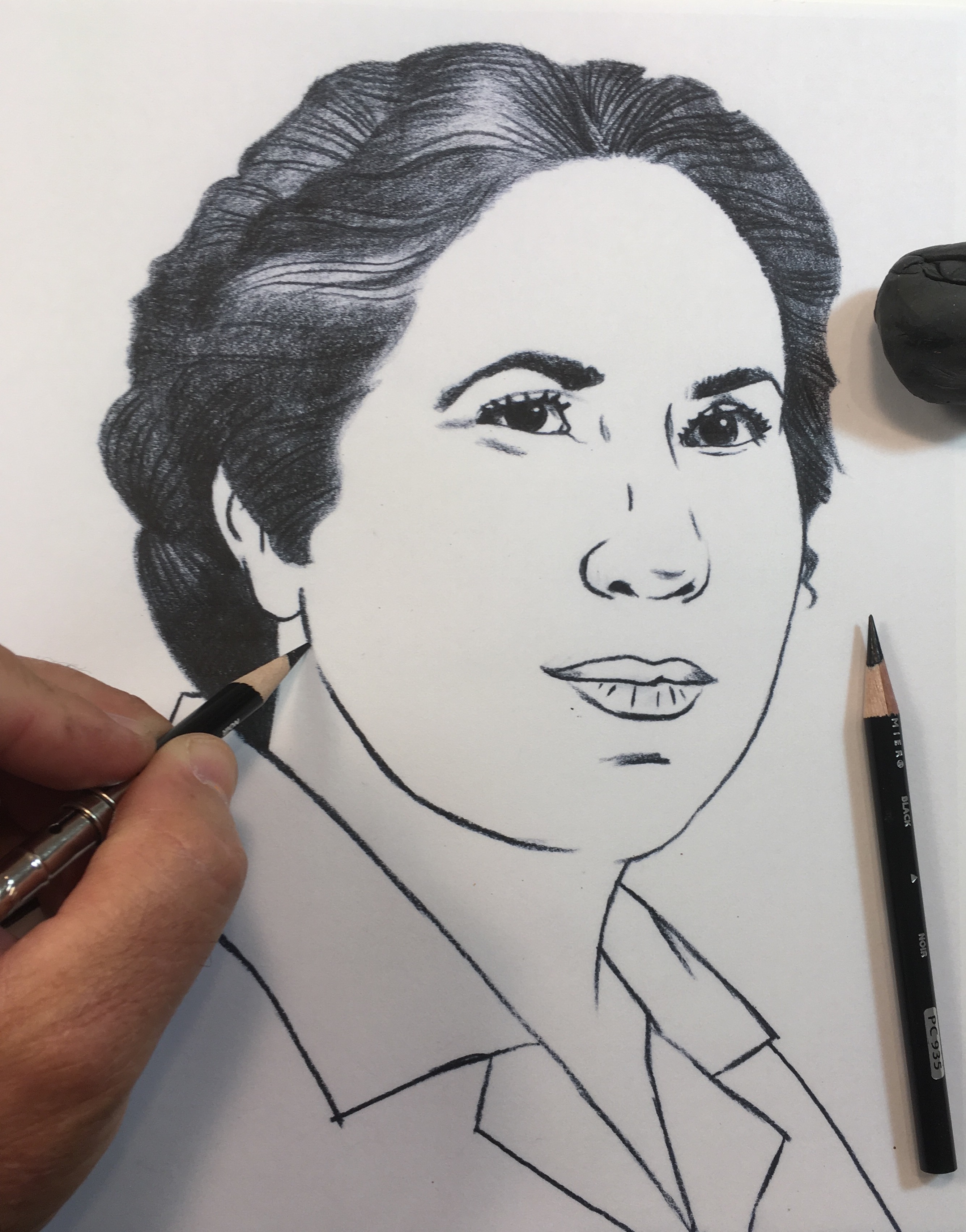

Drawing the portrait of Fabiola for the book Bravo! Poems about Amazing Hispanics.

For Hispanic Heritage Month let’s travel to New Mexico to meet FABIOLA CABEZA DE BACA [1894-1991] who descended from Spanish explorers. She was an American activist, nutritionist, writer and teacher who applied a bilingual approach to her classes adding Latino and Native American history to standard coursework.

Her family, the Cabeza de Bacas traced their heritage back to New Mexico explorer Alvar Nunez Cabeza de Vaca. In 1912, her uncle was elected and served as the first Lieutenant Governor for the State of New Mexico and went on to become the second Governor of the state. When her mother died in 1898, she and her three siblings were raised by their father and paternal grandmother. As a child, she grew up wealthy on the family ranch in northeast New Mexico. The women in her family did not perform manual labor but focused on charity work and supervising servants. Fabiola rejected typical gender roles choosing to ride her pony beside the horses of her father and grandfather. When the siblings reached school age, they moved from the ranch with their grandmother to a mansion. Fabiola longed for the summers when she could hang out with her dad and uncles and escape the needle work her grandmother prescribed. She was sent to study at a Catholic school but was expelled after a confrontation with the nuns in her very first year. Fabiola landed in a public high school, then in 1906 traveled to Spain to study language and history. In 1913 she finished high school with her teaching certificate and despite her father’s protests went to work at a rural one room school house.

Fabiola at the rural New Mexico schoolhouse where she taught diverse children, circa 1916.

As it was far from her family ranch, she boarded with a local family. The diverse children who attended her school were very different from her own upbringing. They had challenging lives and could participate in school for only part of the year in order to help their struggling families. Fabiola bought her own school materials, taught with out of date books, no bathrooms or running water. She embraced her student’s varied backgrounds that included Spanish speakers with Indian blood, Spanish ancestry and homesteaders. During music class she encouraged the kids to share songs they knew from cowboy and hillbilly tunes to Spanish folk songs.

After getting her degree from the New Mexico public school system in Pedagogy and Romance languages she became intrigued with Home Economics. Fabiola connected to the idea of bringing both science and productivity to families. She enrolled in a variety of classes including foods, clothing, and chemistry. After moving to Las Cruces she secured her degree in Home Economics from New Mexico State University. It was then that Fabiola began her work as an extension agent in New Mexico for Hispanic and Pueblo villages. She brought learning activities to rural locations teaching women modern agricultural techniques, introducing them to sewing machines and organizing clubs. Determined to help rural families thrive, she was dedicated to her work for thirty years. Cabeza de Baca was the first agent to speak Spanish and translated government information to the people she visited. Fabiola was also the first agent sent out to Pueblos in the Southwest. The Smith-Lever Act and Smith-Hughs Act of 1914 and 1917 sought to motivate rural Americans to stay on farms instead of heading to big cities for jobs. They did this by improving rural lives using science. Even before the Great Depression, the state of New Mexico stood out with 82% of the population living in poverty. Sixty percent of rural women were Spanish, and as the only Spanish speaking agent, she had plenty of work from daylight to darkness.

Fabiola taught gardening, canning, sewing, home repair, even instructing rural residents on how to raise chickens. Because Fabiola valued tradition, she connected to her clients by combining the old with the new. One example was her integration contemporary sewing machines with traditional crafts like quilting. She importantly advanced food safety in the southwest teaching rural people in New Mexico to can, dry, and preserve food. These practices made it last longer and decreased the risk of food borne illnesses. She is also credited with organizing markets for Native American women to sell handmade goods for profit. Fabiola married an insurance agent Carlos Gilbert who was also an activist in the League of United Latin American Citizens. After ten years together, they divorced but their partnership fueled her participation in the civil rights movement for Hispanics. Fabiola also served her community as president of the Santa Fe Ladies Council.

In 1932, her car was struck by a train injuring her leg which was later amputated. Not willing to let tragedy slow her down, she kept busy and was back on the road in just two years as an extension agent. Fabiola traversed rural New Mexico and took time to keep incredible notes about local traditions. She recorded everything from herbal remedies to recipes and documented religious traditions. Some of her writing was published in the Nuevo Mexicana, a Santa Fe newspaper. With great energy, she also created a radio program that connected to homemakers. Fabiola loved to cook and her recipes included Indian, Mexican, Spanish and Anglo ideas. When her book Historic Cookery was published, it was sent out to other governors to garner publicity for New Mexico. This book targeted an Anglo audience and brought attention to the earthy, hearty, simple Southwestern cuisine, prepared mostly with regional ingredients, such as chiles, beans, squash and corn. The Good Life: New Mexico Traditions and Foods was her second cookbook and put recipes in both historic and cultural contexts.

In the 1940’s, Cabeza de Baca began to write as a form of social action detailing the cultural traditions of New Mexican villages. Her book, We Fed Them Cactus came out in 1954 telling the stories of four generations of family history in the Southwest. After retirement and as part of the United Nations she created economic programs for Mexico, training workers in techniques she learned working in pueblos and villages. In 1959 she retired to consult for the Peace Corps and became part of La Sociedad Folklorica of Santa Fe, a group dedicated to the preservation of Spanish folklore and culture.

Final portrait for Bravo! Poems about Amazing Hispanics written by Margarita Engle. Fabiola at home in the Southwest.